[The numbers in square brackets are references. 😇]

Vitamin B12

In the pictures below you can see a vitamin B12 supplement which is commonly available in Bangladesh. It contains 200 µg (= mcg = micrograms) per tablet. The cost should be about 240 Taka for 30 tablets. It's called "Neuro-B".

If you are vegan, you can choose one of these options [1–4]:

- About 1/4 tablet (50 µg vitamin B12) every day (cost: 60 Taka per month) [5, 6,10–15]

- 1 tablet (200 µg vitamin B12) every other day (cost: about 120 Taka per month) [7,11,12,16–18]

If you want to make it cheaper, you can also nibble a little bit off the tablet every day and in this way consume only 1 tablet per month. That means, you would take ...

- ... about 1/30 (one thirtieth) of a tablet (i.e. about 6 or 7 µg vitamin B12) every day. Of course, you cannot do this precisely. But if you nibble off a small bit off the tablet every day, and you end up using 1 or 2 or 3 tablets per month, this would only cost you about 8 to 24 Taka per month [5, 6,10–15].

You can take vitamin B12 supplements with or without your meals.

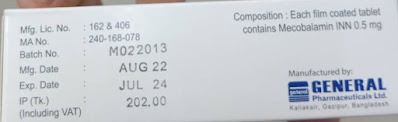

This is another vitamin B12 supplement available in Bangladesh (thanks, Samira!). This supplement contains 500 micrograms (= 500 µg = 0.5 mg) of vitamin B12 per tablet. That means: take four of these per week (all at once or on different days - as you like).

Calcium

Choose at least one of the following options daily. These foods are rich in calcium and have good calcium bioavailability:- tofu made with calcium

- Chinese cabbage (China kopi, pak choi, bok choy) [~90 mg calcium/100 g cooked]

- Napa cabbage (nati shak, petsai) [~30 mg calcium/100 g cooked]

- China shak (saishin, choy sum)

- mustard greens (mustard spinach, sarisa shak, shorshe shak)

- Malabar spinach (pui shak) [~120 mg calcium/100 g cooked]

- turnip greens (shalgom)

- radish greens (mula shak)

- water spinach (kolmi shak) [~50 mg calcium/100 g cooked]

- broccoli

- moringa leaves [~190 mg calcium/100 g cooked]

- moringa leaf powder [~200 mg calcium/10 g] (Gopalakrishnan et al. 2016)

- sweet potato leaves

- sweet bitter melon leaves (lau shak)

- pumpkin leaves (pumpkin shak, kumra shak)

- Jute mallow leaves (Jute spinach, pat shak) [~40 mg calcium/100 g cooked]

- bathua leaves (lambsquarters, lamb's quarters, Chenopodium album) [~260 mg calcium/100 g cooked]

- helencha leaves (Enhydra fluctuans) [~90 mg calcium/100 g cooked - but it can also be high in lead (Murtaja et al. 2014)]

- calcium-fortified bread - not very widely available, however

These foods are good sources of calcium - but only if you eat some of these on a daily basis and in medium-sized to large portions, for example about 1 cup (about 200 g) of tofu per day or about 1 to 2 cups of dark green leaves vegetables (the ones listed above) per day (1 to 2 cups is the volume of the cooked vegetables).

Note that data shak (amaranth leaves, "stem spinach") and palong shak (spinach) are not good sources of calcium because they are high in oxalic acid (which reduces calcium bioavailability). Boiling them and discarding the cooking water will probably at least somewhat decrease the oxalic acid content. In any case, data shak and palong shak are very healthy foods that are rich in many nutrients which can help keeping your body, including your bones, healthy.

A note on official calcium recommendations (given by nutrition societies):

In many (especially "western" countries), the dietary reference intake for calcium is about 1000 mg/day for adults (in Bangladesh, the same amount has been suggested, see Table 1 in Bromage et al. 2017). The Nutrition Society of Bangladesh's website is currently unavailable. The 1000 mg/day recommendation is based on the so-called "estimate average requirement", which is 800 mg/day, to which a certain amount is added (mathematically) in order to make sure that those people with higher calcium needs (not everyone has exactaly the same needs) will also get enough (EFSA 2015). In some countries, the intake recommendation is lower, for example, 700 mg/day (for adults) in the United Kingdom (BDA 2023, NHS 2020, BNF 2005). The exact amount of calcium that would be ideal is being controversially discussed. But, in my opinion, for the time being it would be a good idea to aim for least ~600 or 700 mg/day, and maybe the recommended 1000 mg/day would be even better.

Main source of calcium for average omnivores in Bangladesh:

"Fish, milk, vegetables, and rice are important sources of calcium in Bangladesh, the first 3 by virtue of their nutrient density and rice by its high consumption" (Bromage et al. 2017). When they say fish, they mean small fishes that are eaten with the bones, for example, Chapila fishes.

Other calcium sources:

Apart from the vegan sources listed above, and supplements, this is an interesting suggestion: "Home fortification by way of micronutrient powders may be an effective option for improving calcium status in Bangladeshi children. Locally, there are proven concerns around these powders’ palatability in comparison with tablets, their ease of distribution, and to what degree calcium will interfere with iron absorption [large amounts of calcium, e.g., 1000 mg tablets taken with meals, can decrease iron absorption]. A less expensive alternative may involve the addition of locally sourced calcium salts (slated lime [I think, it should be "slaked lime", i.e., calcium hydroxide]) to rice while it is being cooked. Traditional fortification of corn with lime has been shown to increase the amount of calcium within and absorbed from [so-called nixtamalized corn] tortillas among Mexican women and has been implicated in reduced rates of preeclampsia among the Mayan Indians of Guatemala since 1980 [Nixtamalization has been used for thousands of years in central America, long before Europeans arrived]. We observed that home fortification of rice with lime is practiced in Chakaria [in Cox's Bazar District, Bangladesh], where it is promoted by the local nongovernmental organization Social Assistance and Rehabilitation for the Physically Vulnerable (SARPV) to prevent and ameliorate rickets. Any antirachitic [prevening or treating rickets] effects of liming on rice have yet to be studied, however, and there is a need for research on the food composition, bioavailability, efficacy, and acceptability of lime-fortified rice." (Bromage et al. 2017).

The Dietary Guidelines for Indians (NIN 2011), include these vegetables as potential calcium sources: amaranth leaves, cauliflower greens, curry leaves, knol-khol leaves, Agathi leaves, and Colocasia leaves (NIN 2011), and in an article about Bangladesh I found these green leafy vegetables listed: jute leaves, helencha leaves (Enhydra fluctuans), bathua leaves (Chenopodium album), and danta shak [data shak, amaranth leaves] (Knight et al. 2023). The article by Knight et al. also states that "[l]ocal [..] plant-source foods that are naturally high in calcium could be promoted [...]. [...] Study objective 2: To identify good food sources of calcium for the target population [...]. To answer study objective 2, the best food sources of calcium selected for each target population were those providing at least 5% of the calcium in the target group's Module 2 diet (i.e., nutritionally best diet). The best food sources of calcium were identified from this diet instead of the maximized calcium diet because these foods were also consistent with an overall nutritious diet in which the intake of multiple nutrients was optimized. [...]" Apart from green leafy vegetables (and fish and milk), the article also lists these foods as relevant calcium sources: water gourd, green banana, and potato. In addition, they conclude by highlighting "a need to promote an increase in the consumption of locally available calcium-rich foods from current levels or the development, provision, and promotion of alternative food sources of calcium, such as calcium-fortified products, to ensure population-level dietary calcium adequacy" (Knight et al. 2023).

Insufficient intake of calcium in Bangladesh:

Very low calcium intake is common in Bangladesh: Some studies show "significant calcium inadequacy among young, urban Bangladeshi women" and calcium intake is often as low as ~200 mg/day (Bromage et al. 2017). This shouldn't be a reason for vegans in Bangladesh to think that such a very low calcium intake is just fine.

How can you consume an adequate amount of calcium in Bangaldesh?

The best option is to eat plenty of the foods recommended above (see the list) and to consider taking a supplement that contains ~300 mg of calcium per day (take it with a meal). It's good to also follow the other recommendations in this post because other nutrients are important for your bones too (including vitamin D, protein, iodine, zinc, and vitamin B12).

Vitamin D

Get ...

- ... about 15–30 minutes of sunshine (directly on your skin) every day – or more sunshine less often. Avoid excessive sunshine though, because it can increase your risk of skin cancer (and it can accelerate skin aging).

If you do not get enough sunshine ...

- take a vegan vitamin D supplement with about 1000 IU (25 µg) per day [2,3,23,28,43–50]

Do not take more than 2000 IU (50 µg) of vitamin D per day unless a medical doctor has prescribed this to you.

In Bangladesh there is no “vitamin D winter” at all, i.e. your body can produce vitamin D from sunshine on your skin throughout the year [51].

Iodine

Choose one (not all!) of the following options [2,3,45,52–60]:

Either ...

- ... use iodized salt (1 teaspoon contains about 20–240 µg of iodine – check the label) [61–63]. In Bangladesh, about 1/2 (one half of) a teaspoon of iodized salt (per day) should have a suitable amount of iodine for one adult. ... But try to avoid excessive salt intake and try to consume less than 1 teaspoon of salt per day (including all salt in processed foods).

... or ...

- ... take an iodine supplement with about 75–100 µg per day.

You could also ...

- ... eat seaweed, such as nori or wakame, several times per week - however, seaweed appears to hardly be available in Bangladesh.

Iodine is very important for pregnant or breastfeeding women and for children.

Both iodine deficiency and iodine excess should be avoided.

Iodized salt is just used in food preparation as you would use non-iodized salt.

Iodized salt in Bangladesh (photo from July 2022)

Omega-3 fatty acids

Chia seeds are a good source of omega-3 fatty acids, and they are commonly available and quite affordable in Bangladesh.

Choose one of these options every day [19,30,64–69]. Theses recommendations are for men, who typically eat more food (and more calories) than women. For women a little less is sufficient.

- About 1–2 tablespoons of chia seeds per day [69,72–74]

- About 1–2 tablespoons of tokma seeds (basil seeds, Ocimum basilicum) per day

- About 1–2 teaspoons of linseed oil (flaxseed oil) [64]

Or you can choose one of the following options. But these are probably more expensive:

- About 2 tablespoons of ground linseeds (flaxseeds) [64,70,71]

- About 10 walnuts (= 20 walnut halves; about 40 grams) per day [64]

Hemp seeds, hemp seed oil, and canola (rapeseed) oil are also good sources of omega-3 fatty acids, but these aren't commonly available in Bangladesh.

Vegan EPA/DHA supplements do not seem to be availble in Bangladesh, and there isn’t much evidence for recommending that average vegan should take such a supplement. However, just for information, for those vegans who have access to such a supplement and who wish to take it:

- Use half of the above recommendations (for example, half a tablespoon of chia seeds per day) – and add a vegan DHA supplement containing about 200–300 mg DHA every two or three days (or every day if you like) [64,67–69,75–77].

Iron

Legumes (beans, lentils, chickpeas, peanuts) are good sources of iron [26,78,79].

Iron is especially important for menstruating women and children.

Additional tips:

Sesame seeds, peanuts, and cashew nuts are probably the cheapest option in Bangladesh.

Additional tips:

- Consuming vitamin C at the same time as iron rich foods increases the absorption of iron from plant sources [78,80–83].

- Drinking coffee or tea with meals lowers the absorption of iron [80–84].

- Cooking tomato sauce (or other sauces that are slightly acidic) in cast iron cookware increases the amount of iron in the sauce [83–86].

Zinc

Legumes (beans, lentils, chickpeas, peanuts), whole grains, and nuts are good sources of zinc [2,30,87,88].These foods are especially rich in zinc:

- Sesame seeds - These should be ground up. Otherwise you might not be able to digest them well.

- Cashew nuts

- Sunflower seeds

- Pumpkin seeds

Selenium

In some parts of the world (for example much of Europe), the soils are low in selenium. But this seems to be less of a problem in Bangladesh.

These foods are probably quite good sources of selenium in Bangladesh:

Especially ...

- Sesame seeds - These should be ground up. Otherwise you might not be able to digest them well.

But also ...

- Cashew nuts

- Peanuts

- Coconut "meat"

... and also (if available) ...

- Sunflower seeds

- Pumpkin seeds

- Pistachios

- Macadamia nuts

Vitamin A

Dark green vegetables, orange-coloured fruits and orange-coloured vegetables are good sources of provitamin A which the body can convert to vitamin A [3,45,105].

Great provitamin A sources are, for example:

- cooked carrots

- carrot juice

- pumpkin

- orange-coloured sweet potatoes

- any dark green leafy vegetables

- mangoes

- papayas

- red bell peppers

Protein

Legumes (beans, lentils, chickpeas, soybean chunks, ...) are the protein staples of vegan diets. In addition, whole grains, nuts and seeds will supply protein [3,106–108].

Legumes and grains together (for example, rice and beans, bread and lentils, etc.) supply "complete protein" (like animal-source foods). We don't have to necessarily eat the legumes and grains at the same meal.

You should also consume enough calories. Most vegans eat enough calories. But if you don’t eat enough calories, your body will use the protein you eat as calories, and you might end up with too little protein and then you might lose muscle mass.

The "limiting" amino acid (protein building blocks) of vegan diets is lysine. But legumes are rich in lysine. That's why legumes are a great "replacement" of animal-source high-protein foods (meat, fish, eggs, dairy). Grains are rich in the amino acid methionine.

What if you are overweight?

... and want to lose weight (body fat) ... Have a look here.

What if you are underweight?

... and want to gain weight (some muscle and maybe some body fat too) ... Have a look here.

These recommendations have recently been published in the scientific literature.

References

1. Johnsen, J. B. & Fønnebø, V. Vitamin B12-mangel ved strengt vegetabilsk kosthold. Hvorfor følger noen et slikt kosthold, og hva vil de gjøre ved B12-mangel? Abstract. Tidsskrift for den Norske laegeforening tidsskrift for praktisk medicin, ny raekke 111, 1, 62–64 (1991)

2. Schüpbach, R., Wegmüller, R., Berguerand, C. et al. Micronutrient status and intake in omnivores, vegetarians and vegans in Switzerland. European journal of nutrition 56, 1, 283–293 (2017)

3. Sobiecki, J. G., Appleby, P. N., Bradbury, K. E. et al. High compliance with dietary recommendations in a cohort of meat eaters, fish eaters, vegetarians, and vegans: results from the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition-Oxford study. Nutrition research (New York, N.Y.) 36, 5, 464–477 (2016)

4. Woo, K. S., Kwok, T. C. Y., Celermajer, D. S. Vegan diet, subnormal vitamin B-12 status and cardiovascular health. Nutrients 6, 8, 3259–3273 (2014)

5. Bor, M. V., Castel-Roberts, K. M. von, Kauwell, G. P. et al. Daily intake of 4 to 7 microg dietary vitamin B-12 is associated with steady concentrations of vitamin B-12-related biomarkers in a healthy young population. The American journal of clinical nutrition 91, 3, 571–577 (2010)

6. Carmel R (2006) Cobalamin (Vitamin B12). In Modern nutrition in health and disease. 10th ed., pp. 482–497, [Shils ME, Shike M and Ross AC et al., editors]. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins

7. Institute of Medicine (IOM) (1998) Dietary reference intakes for Thiamin, Riboflavin, Niacin, Vitamin B6, Folate, Vitamin B12, Papntothenic Acid, Biotin, and Choline: A report of the Standing Committee on the Scientific Evaluation of Dietary Reference Intakes Food and Nutrition Board, Institute of Medicine. Washington DC: Nat. Acad. Press

8. Luhby AL, Cooperman JM, Donnenfeld AM: Herrero JM et al. Observations on transfer of vitamin B12 from mother to fetus and newborn. Am J Dis Child 96, 532–533 (1958)

9. Norris J: Rationale for VeganHealth’s B12 Recommendations. (2022) https://veganhealth.org/vitamin-b12/explanation-of-vitamin-b12-recommendations/ (22 July 2023)

10. Haddad, E. H., Berk, L. S., Kettering, J. D. et al. Dietary intake and biochemical, hematologic, and immune status of vegans compared with nonvegetarians. The American journal of clinical nutrition 70, 3 Suppl, 586 (1999)

11. Heyssel, R. M., Bozian, R. C., Darby, W. J. et al. Vitamin B12 turnover in man. The assimilation of vitamin B12 from natural foodstuff by man and estimates of minimal daily dietary requirements. The American journal of clinical nutrition 18, 3, 176–184 (1966)

12. Obeid, R., Fedosov, S. N., Nexo, E. Cobalamin coenzyme forms are not likely to be superior to cyano- and hydroxyl-cobalamin in prevention or treatment of cobalamin deficiency. Molecular nutrition & food research 59, 7, 1364–1372 (2015)

13. Adams, J. F., Ross, S. K., Mervyn, L. et al. Absorption of cyanocobalamin, coenzyme B 12 methylcobalamin, and hydroxocobalamin at different dose levels. Scandinavian journal of gastroenterology 6, 3, 249–252 (1971)

14. Carmel, R. Mandatory fortification of the food supply with cobalamin: an idea whose time has not yet come. Journal of inherited metabolic disease 34, 1, 67–73 (2011)

15. Deshmukh, U. S., Joglekar, C. V., Lubree, H. G. et al. Effect of physiological doses of oral vitamin B12 on plasma homocysteine: a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind trial in India. European journal of clinical nutrition 64, 5, 495–502 (2010)

16. Berlin, H., Berlin, R., Brante, G. Oral treatment of pernicious anemia with high doses of vitamin B12 without intrinsic factor. Acta medica Scandinavica 184, 4, 247–258 (1968)

17. Donaldson, M. S. Metabolic vitamin B12 status on a mostly raw vegan diet with follow-up using tablets, nutritional yeast, or probiotic supplements. Annals of nutrition & metabolism 44, 5-6, 229–234 (2000)

18. Gomollón, F., Gargallo, C. J., Muñoz, J. F. et al. Oral Cyanocobalamin is Effective in the Treatment of Vitamin B12 Deficiency in Crohn's Disease. Nutrients 9, 3 (2017)

19. Appleby, P. N. & Key, T. J. The long-term health of vegetarians and vegans. The Proceedings of the Nutrition Society 75, 3, 287–293 (2016)

20. Appleby, P., Roddam, A., Allen, N. et al. Comparative fracture risk in vegetarians and nonvegetarians in EPIC-Oxford. European journal of clinical nutrition 61, 12, 1400–1406 (2007)

21. Dyett, P., Rajaram, S., Haddad, E. H. et al. Evaluation of a validated food frequency questionnaire for self-defined vegans in the United States. Nutrients 6, 7, 2523–2539 (2014)

22. Fang, A., Li, K., Guo, M. et al. Long-Term Low Intake of Dietary Calcium and Fracture Risk in Older Adults With Plant-Based Diet: A Longitudinal Study From the China Health and Nutrition Survey. Journal of bone and mineral research the official journal of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research 31, 11, 2016–2023 (2016)

23. Mangels, A. R. Bone nutrients for vegetarians. The American journal of clinical nutrition 100 Suppl 1, 469 (2014)

24. Morales-Torres, J. & Gutiérrez-Ureña, S. The burden of osteoporosis in Latin America. Osteoporosis international a journal established as result of cooperation between the European Foundation for Osteoporosis and the National Osteoporosis Foundation of the USA 15, 8, 625–632 (2004)

25. Nachshon, L. & Katz, Y. [The importance of "milk bones" to "wisdom bones" - cow milk and bone health - lessons from milk allergy patients.] Abstract. Harefuah 155, 3, 163 (2016)

26. Rizzo, N. S., Jaceldo-Siegl, K., Sabate, J. et al. Nutrient profiles of vegetarian and nonvegetarian dietary patterns. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics 113, 12, 1610–1619 (2013)

27. Thorpe, D. L., Knutsen, S. F., Beeson, W. L. et al. Effects of meat consumption and vegetarian diet on risk of wrist fracture over 25 years in a cohort of peri- and postmenopausal women. Public health nutrition 11, 6, 564–572 (2008)

28. Tucker, K. L. Vegetarian diets and bone status. The American journal of clinical nutrition 100 Suppl 1, 329S-35S (2014)

29. Messina, V. & Messina, M. Soy products as sources of calcium in the diets of chinese americans. Journal of the American Dietetic Association 110, 12, 1812-3; author reply 1813 (2010)

30. Reid, M. A., Marsh, K. A., Zeuschner, C. L. et al. Meeting the nutrient reference values on a vegetarian diet. The Medical journal of Australia 199, 4 Suppl, 40 (2013)

31. Weaver, C. M., Proulx, W. R., Heaney, R. Choices for achieving adequate dietary calcium with a vegetarian diet. The American journal of clinical nutrition 70, 3 Suppl, 543 (1999)

32. de Abajo, Francisco J. de, Rodríguez-Martín, S., Rodríguez-Miguel, A. et al. Risk of Ischemic Stroke Associated With Calcium Supplements With or Without Vitamin D: A Nested Case-Control Study. Journal of the American Heart Association 6, 5 (2017)

33. Böhmer, H., Müller, H., Resch, K. L. Calcium supplementation with calcium-rich mineral waters: a systematic review and meta-analysis of its bioavailability. Osteoporosis international a journal established as result of cooperation between the European Foundation for Osteoporosis and the National Osteoporosis Foundation of the USA 11, 11, 938–943 (2000)

34. Vitoria, I., Maraver, F., Ferreira-Pêgo, C. et al. The calcium concentration of public drinking waters and bottled mineral waters in Spain and its contribution to satisfying nutritional needs. Nutricion hospitalaria 30, 1, 188–199 (2014)

35. Bressani, R., Turcios, J. C., Colmenares de Ruiz, A. S. et al. Effect of processing conditions on phytic acid, calcium, iron, and zinc contents of lime-cooked maize. Journal of agricultural and food chemistry 52, 5, 1157–1162 (2004)

36. Hambidge, K. M., Krebs, N. F., Westcott, J. L. et al. Absorption of calcium from tortilla meals prepared from low-phytate maize. The American journal of clinical nutrition 82, 1, 84–87 (2005)

37. Islas-Rubio, A. R., La Barca, A. M. C. de, Molina-Jacott, L. E. et al. Development and evaluation of a nutritionally enhanced multigrain tortilla snack. Plant foods for human nutrition (Dordrecht, Netherlands) 69, 2, 128–133 (2014)

38. Monárrez-Espino J, Béjar-Lío GI, Vázquez-Mendoza G Adecuación de la dieta servida a escolares en albergues indigenistas de la Sierra Tarahumara, México. Salud Pública Méx 52, 23–29 (2010)

39. Pappa, M. R., Palomo, P. P. de, Bressani, R. Effect of lime and wood ash on the nixtamalization of maize and tortilla chemical and nutritional characteristics. Plant foods for human nutrition (Dordrecht, Netherlands) 65, 2, 130–135 (2010)

40. Rosado, J. L., López, P., Morales, M. et al. Bioavailability of energy, nitrogen, fat, zinc, iron and calcium from rural and urban Mexican diets. The British journal of nutrition 68, 1, 45–58 (1992)

41. Rosado, J. L., Díaz, M., Rosas, A. et al. Calcium absorption from corn tortilla is relatively high and is dependent upon calcium content and liming in Mexican women. The Journal of nutrition 135, 11, 2578–2581 (2005)

42. Serna-Saldivar, S. O., Amaya Guerra, C. A., Herrera Macias, P. et al. Evaluation of the lime-cooking and tortilla making properties of quality protein maize hybrids grown in Mexico. Plant foods for human nutrition (Dordrecht, Netherlands) 63, 3, 119–125 (2008)

43. Holick, M. F. The vitamin D deficiency pandemic: Approaches for diagnosis, treatment and prevention. Reviews in endocrine & metabolic disorders (2017)

44. Ho-Pham, L. T., Vu, B. Q., Lai, T. Q. et al. Vegetarianism, bone loss, fracture and vitamin D: a longitudinal study in Asian vegans and non-vegans. European journal of clinical nutrition 66, 1, 75–82 (2012)

45. Kristensen, N. B., Madsen, M. L., Hansen, T. H. et al. Intake of macro- and micronutrients in Danish vegans. Nutrition journal 14, 115 (2015)

46. Outila, T. A., Kärrkkäinen, M. U. M., Seppänen, R. H. et al. Dietary Intake of Vitamin D in Premenopausal, Healthy Vegans was Insufficient to Maintain Concentrations of Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D and Intact Parathyroid Hormone Within Normal Ranges During the Winter in Finland. Journal of the American Dietetic Association 100, 4, 434–441 (2000)

47. Plehwe, W. E. & Carey, R. P. L. Spinal surgery and severe vitamin D deficiency. The Medical journal of Australia 176, 9, 438–439 (2002)

48. Smith, T. J., Tripkovic, L., Damsgaard, C. T. et al. Estimation of the dietary requirement for vitamin D in adolescents aged 14-18 y: a dose-response, double-blind, randomized placebo-controlled trial. The American journal of clinical nutrition 104, 5, 1301–1309 (2016)

49. Ustianowski, A., Shaffer, R., Collin, S. et al. Prevalence and associations of vitamin D deficiency in foreign-born persons with tuberculosis in London. The Journal of infection 50, 5, 432–437 (2005)

50. Vidailhet, M., Mallet, E., Bocquet, A. et al. Vitamin D: still a topical matter in children and adolescents. A position paper by the Committee on Nutrition of the French Society of Paediatrics. Archives de pediatrie organe officiel de la Societe francaise de pediatrie 19, 3, 316–328 (2012)

51. Jäpelt, R. B. & Jakobsen, J. Vitamin D in plants: a review of occurrence, analysis, and biosynthesis. Frontiers in plant science 4, 136 (2013)

52. Davidsson, L. Are vegetarians an 'at risk group' for iodine deficiency? The British journal of nutrition 81, 1, 3–4 (1999)

53. Elorinne, A.-L., Alfthan, G., Erlund, I. et al. Food and Nutrient Intake and Nutritional Status of Finnish Vegans and Non-Vegetarians. PloS one 11, 2, e0148235 (2016)

54. Fields, C., Dourson, M., Borak, J. Iodine-deficient vegetarians: a hypothetical perchlorate-susceptible population? Regulatory toxicology and pharmacology RTP 42, 1, 37–46 (2005)

55. Krajcovicová-Kudlácková, M., Bucková, K., Klimes, I. et al. Iodine deficiency in vegetarians and vegans. Annals of nutrition & metabolism 47, 5, 183–185 (2003)

56. Leung, A. M., Lamar, A., He, X. et al. Iodine status and thyroid function of Boston-area vegetarians and vegans. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism 96, 8, E1303-7 (2011)

57. Lightowler, H. J. & Davies, G. J. Assessment of iodine intake in vegans: weighed dietary record vs duplicate portion technique. European journal of clinical nutrition 56, 8, 765–770 (2002)

58. Lightowler, H. J. & Davies, G. J. Iodine intake and iodine deficiency in vegans as assessed by the duplicate-portion technique and urinary iodine excretion. The British journal of nutrition 80, 6, 529–535 (1998)

59. Kanaka, C., Schütz, B., Zuppinger, K. A. Risks of alternative nutrition in infancy: a case report of severe iodine and carnitine deficiency. European journal of pediatrics 151, 10, 786–788 (1992)

60. Remer, T., Neubert, A., Manz, F. Increased risk of iodine deficiency with vegetarian nutrition. The British journal of nutrition 81, 1, 45–49 (1999)

61. García-Casal, M. N., Landaeta, M., Adrianza de Baptista, G. et al. Valores de referencia de hierro, yodo, zinc, selenio, cobre, molibdeno, vitamina C, vitamina E, vitamina K, carotenoides y polifenoles para la población venezolana. Archivos latinoamericanos de nutricion 63, 4, 338–361 (2013)

62. Rohner, F., Zimmermann, M., Jooste, P. et al. Biomarkers of nutrition for development--iodine review. The Journal of nutrition 144, 8, 1322S-1342S (2014)

63. Zimmermann, M. B. & Andersson, M. Assessment of iodine nutrition in populations: past, present, and future. Nutrition reviews 70, 10, 553–570 (2012)

64. Davis, B. C. & Kris-Etherton, P. M. Achieving optimal essential fatty acid status in vegetarians: current knowledge and practical implications. The American journal of clinical nutrition 78, 3 Suppl, 640 (2003)

65. Domenichiello, A. F., Chen, C. T., Trepanier, M.-O. et al. Whole body synthesis rates of DHA from α-linolenic acid are greater than brain DHA accretion and uptake rates in adult rats. Journal of lipid research 55, 1, 62–74 (2014)

66. Fayet-Moore, F., Baghurst, K., Meyer, B. J. Four Models Including Fish, Seafood, Red Meat and Enriched Foods to Achieve Australian Dietary Recommendations for n-3 LCPUFA for All Life-Stages. Nutrients 7, 10, 8602–8614 (2015)

67. Harris, W. S. Achieving optimal n-3 fatty acid status: the vegetarian's challenge… or not. The American journal of clinical nutrition 100 Suppl 1, 449S-52S (2014)

68. Sanders, T. A. B. DHA status of vegetarians. Prostaglandins, leukotrienes, and essential fatty acids 81, 2-3, 137–141 (2009)

69. Saunders, A. V., Davis, B. C., Garg, M. L. Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids and vegetarian diets. Med J Aust 1, 2, 22–26 (2012)

70. Demark-Wahnefried, W., Polascik, T. J., George, S. L. et al. Flaxseed supplementation (not dietary fat restriction) reduces prostate cancer proliferation rates in men presurgery. Cancer epidemiology, biomarkers & prevention a publication of the American Association for Cancer Research, cosponsored by the American Society of Preventive Oncology 17, 12, 3577–3587 (2008)

71. Hackshaw-McGeagh, L. E., Perry, R. E., Leach, V. A. et al. A systematic review of dietary, nutritional, and physical activity interventions for the prevention of prostate cancer progression and mortality. Cancer causes & control CCC 26, 11, 1521–1550 (2015)

72. EFSA Opinion on the safety of ‘Chia seeds (Salvia hispanica L.) and ground whole Chia seeds’ as a food ingredient. EFSA Journal 7, 4, 996 (2009)

73. Mohd Ali, N., Yeap, S. K., Ho, W. Y. et al. The promising future of chia, Salvia hispanica L. Journal of biomedicine & biotechnology 2012, 171956 (2012)

74. Ullah, R., Nadeem, M., Khalique, A. et al. Nutritional and therapeutic perspectives of Chia (Salvia hispanica L.): a review. Journal of food science and technology 53, 4, 1750–1758 (2016)

75. Cottin, S. C., Sanders, T. A., Hall, W. L. The differential effects of EPA and DHA on cardiovascular risk factors. The Proceedings of the Nutrition Society 70, 2, 215–231 (2011)

76. Geppert, J., Kraft, V., Demmelmair, H. et al. Microalgal docosahexaenoic acid decreases plasma triacylglycerol in normolipidaemic vegetarians: a randomised trial. The British journal of nutrition 95, 4, 779–786 (2006)

77. Sarter, B., Kelsey, K. S., Schwartz, T. A. et al. Blood docosahexaenoic acid and eicosapentaenoic acid in vegans: Associations with age and gender and effects of an algal-derived omega-3 fatty acid supplement. Clinical nutrition (Edinburgh, Scotland) 34, 2, 212–218 (2015)

78. Waldmann, A., Koschizke, J. W., Leitzmann, C. et al. Dietary iron intake and iron status of German female vegans: results of the German vegan study. Annals of nutrition & metabolism 48, 2, 103–108 (2004)

79. Gorczyca, D., Prescha, A., Szeremeta, K. et al. Iron status and dietary iron intake of vegetarian children from Poland. Annals of nutrition & metabolism 62, 4, 291–297 (2013)

80. Craig, W. J. Iron status of vegetarians. The American journal of clinical nutrition 59, 5 Suppl, 1233 (1994)

81. Gibson, R. S., Heath, A.-L. M., Szymlek-Gay, E. A. Is iron and zinc nutrition a concern for vegetarian infants and young children in industrialized countries? The American journal of clinical nutrition 100 Suppl 1, 459S-68S (2014)

82. Hurrell, R. & Egli, I. Iron bioavailability and dietary reference values. The American journal of clinical nutrition 91, 5, 1461S-1467S (2010)

83. Hunt, J. R. Moving toward a plant-based diet: are iron and zinc at risk? Nutrition reviews 60, 5 Pt 1, 127–134 (2002)

84. Hunt, J. R. Bioavailability of iron, zinc, and other trace minerals from vegetarian diets. The American journal of clinical nutrition 78, 3 Suppl, 633 (2003)

85. Quintaes, K. D., Amaya-Farfan, J., Tomazini, F. M. et al. Mineral Migration and Influence of Meal Preparation in Iron Cookware on the Iron Nutritional Status of Vegetarian Students. Ecology of Food and Nutrition 46, 2, 125–141 (2007)

86. Sanders TAB (2012) Vegetarian diets. In Human nutrition. 12th ed., pp. 355–363, [Geissler CA and Powers HJ, editors]. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone Elsevier

87. Ball, M. J. & Ackland, M. L. Zinc intake and status in Australian vegetarians. The British journal of nutrition 83, 1, 27–33 (2000)

88. Saunders, A. V., Craig, W. J., Baines, S. K. Zinc and vegetarian diets. Med J Aust 1, 2, 17–21 (2012)

89. Hildbrand SM (2015) Bedeutung des Jod/Selen-Quotienten und des Ferritins für das Auftreten einer Autoimmunthyreoiditis (AIT) bei omnivor, lakto-vegetarisch und vegan sich ernährenden Personen: Eine epidemiologische klinische Querschnittstudie. Dissertation zum Erwerb des Doktorgrades der Medizin, Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität

90. Hoeflich, J., Hollenbach, B., Behrends, T. et al. The choice of biomarkers determines the selenium status in young German vegans and vegetarians. The British journal of nutrition 104, 11, 1601–1604 (2010)

91. Lightowler, H. J. & Davies, G. J. Micronutrient intakes in a group of UK vegans and the contribution of self-selected dietary supplements. The journal of the Royal Society for the Promotion of Health 120, 2, 117–124 (2000)

92. Thomson, C. D., Chisholm, A., McLachlan, S. K. et al. Brazil nuts: an effective way to improve selenium status. The American journal of clinical nutrition 87, 2, 379–384 (2008)

93. Colpo, E., Vilanova, C. D. d. A., Brenner Reetz, L. G. et al. A single consumption of high amounts of the Brazil nuts improves lipid profile of healthy volunteers. Journal of nutrition and metabolism 2013, 11348568653185 (2013)

94. Martens, I. B. G., Cardoso, B. R., Hare, D. J. et al. Selenium status in preschool children receiving a Brazil nut-enriched diet. Nutrition (Burbank, Los Angeles County, Calif.) 31, 11-12, 1339–1343 (2015)

95. Dumont, E., Vanhaecke, F., Cornelis, R. Selenium speciation from food source to metabolites: a critical review. Analytical and bioanalytical chemistry 385, 7, 1304–1323 (2006)

96. Benstoem, C., Goetzenich, A., Kraemer, S. et al. Selenium and its supplementation in cardiovascular disease--what do we know? Nutrients 7, 5, 3094–3118 (2015)

97. Ogawa-Wong, A. N., Berry, M. J., Seale, L. A. Selenium and Metabolic Disorders: An Emphasis on Type 2 Diabetes Risk. Nutrients 8, 2, 80 (2016)

98. Thomson, C. D. Assessment of requirements for selenium and adequacy of selenium status: a review. European journal of clinical nutrition 58, 3, 391–402 (2004)

99. Wrobel, J. K., Power, R., Toborek, M. Biological activity of selenium: Revisited. IUBMB life 68, 2, 97–105 (2016)

100. Xia, Y., Hill, K. E., Byrne, D. W. et al. Effectiveness of selenium supplements in a low-selenium area of China. The American journal of clinical nutrition 81, 4, 829–834 (2005)

101. Combs, G. F. Selenium in global food systems. The British journal of nutrition 85, 5, 517–547 (2001)

102. Combs Jr GF & Combs SB (1986) The role of selenium in nutrition. Orlando: Academic Press

103. Mondragón, M. C. & Jaffé, W. G. Consumo de selenio en la ciudad de Caracas en comparación con el de otras ciudades del mundo. Abstract. Archivos latinoamericanos de nutricion 26, 3, 343–352 (1976)

104. Surai PF (2006) Selenium in nutrition and health. Nottingham: Nottingham University Press

105. Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) Nutritional situation in the Americas. Epidemiological bulletin 15, 3, 1–6 (1994)

106. Lousuebsakul-Matthews, V., Thorpe, D. L., Knutsen, R. et al. Legumes and meat analogues consumption are associated with hip fracture risk independently of meat intake among Caucasian men and women: the Adventist Health Study-2. Public health nutrition 17, 10, 2333–2343 (2014)

107. Shams-White, M. M., Chung, M., Du, M. et al. Dietary protein and bone health: a systematic review and meta-analysis from the National Osteoporosis Foundation. The American journal of clinical nutrition 105, 6, 1528–1543 (2017)

108. Marsh, K. A., Munn, E. A., Baines, S. K. Protein and vegetarian diets. Med J Aust 1, 2, 7–10 (2012)